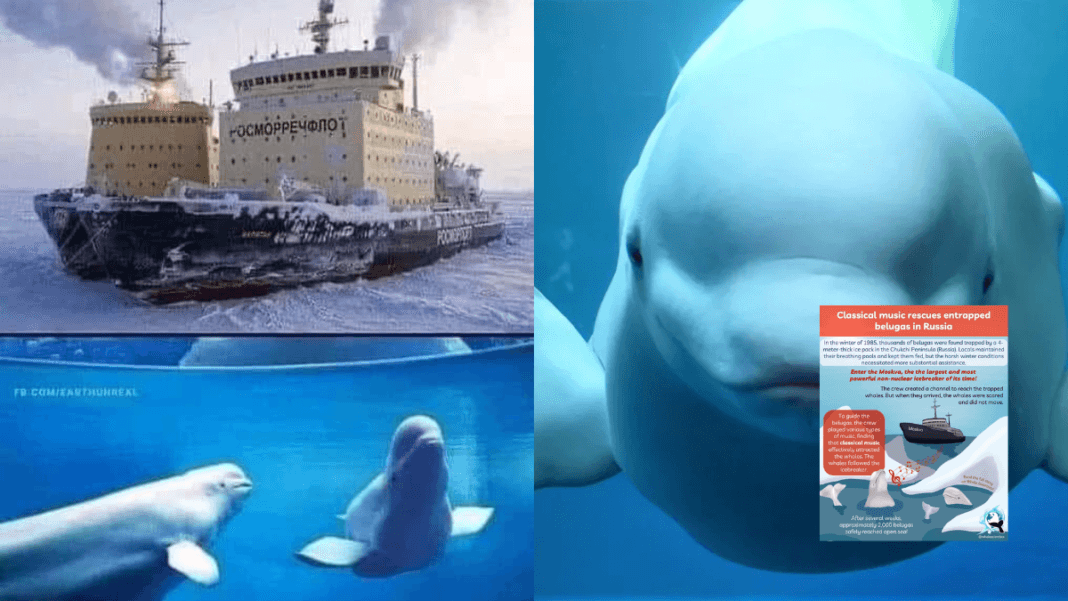

In 1985, the Soviet icebreaker Moskva gained international fame for an unexpected and remarkable rescue operation: it helped guide over 2,000 beluga whales back to the open sea using classical music. Yes, you read that right—classical music played from the ship’s deck.

What is an Icebreaker?

An icebreaker is a type of ship specifically designed to navigate through thick ice, clearing paths where other vessels cannot go. These ships are essential in polar regions, breaking through frozen waters or dense pack ice to open up shipping routes or assist in scientific expeditions. Icebreakers were pivotal in early polar exploration and continue to play a key role in modern Arctic navigation and research.

Moskva: A Powerhouse on the Ice

- Moskva* was one of the most formidable icebreakers ever built. Delivered in 1960, the ship weighed more than 13,000 tons and stretched 122 meters (400 feet) long. Designed with one of the most powerful diesel-electric power plants of its time, it was capable of navigating some of the harshest ice conditions in the world. Its primary role was to escort merchant ships along the treacherous North Sea trade routes.

The ship’s name, Moskva, refers to Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union. The icebreaker served until 1992 when it was decommissioned and sold for scrap.

Operation Beluga – The Rescue Mission

In December 1984, a herd of up to 3,000 beluga whales became trapped in the thick ice near the Chukchi Peninsula in northeastern Russia. A 4-meter thick ice pack had closed off the whales’ path to open water, leaving them confined to small breathing holes. Local hunters initially discovered the herd but soon realized the situation was dire. While the whales were being fed frozen fish and efforts were made to dig out breathing holes, the situation grew worse as temperatures plummeted.

In February 1985, the authorities turned to Moskva for help. The icebreaker was dispatched to break a channel through the thick ice and free the trapped whales before they suffocated or starved. However, when the crew arrived, the ice was so thick that the captain initially called off the mission. As more whales began to perish, however, Moskva powered through, its engines roaring to life as the crew worked tirelessly to clear a path for the animals.

As the operation continued, helicopters dropped fresh fish over the belugas’ breathing holes to sustain them. Despite these efforts, the whales remained reluctant to leave their confined area and approach the open sea.

The Unexpected Solution: Classical Music

With the belugas growing weaker and more hesitant, one crew member suggested trying music, knowing that marine mammals often respond to sound. The crew began playing a range of music from the ship’s deck, experimenting with different genres. To everyone’s surprise, the belugas seemed to react most strongly to classical music, gradually becoming calmer and more willing to approach the ship.

Captain Kovalenko reported that the team’s strategy involved:

- Moving the ship forward and backward in short bursts.

- Breaking the ice in stages.

- Patiently waiting for the whales to follow.

After several attempts, the belugas began to “understand” the ship’s movements and started to follow Moskva as it cleared a path back to the open sea. The operation, dubbed Operation Beluga, took weeks to complete, but by the end of February 1985, an estimated 2,000 whales had successfully made it back to the ocean.

The Cost and Legacy of the Rescue

Operation Beluga cost about $80,000 (roughly $200,000 today), a hefty price for a rescue that many might have thought impossible. Despite the unlikely combination of icebreaking and classical music, the mission was hailed as a success, not only for saving the whales but also for showcasing the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the Moskva crew.

Whether the belugas got a lasting taste for classical music remains a mystery. Still, one thing is certain: Moskva’s remarkable rescue operation will forever be remembered as an extraordinary example of how human ingenuity and the power of sound came together to save an endangered species.

Article Source:NY Times from 1985/ whalescientists